In Pensions Watch edition 5 (January 2021), we predicted that 2021 could be the year that the UK pension

system was propelled up the global rankings, from its lowly and long-standing C+ rating, by the influential annual

Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index.1 Now awarded a prestigious B-grade, for the first time since 2015,2

we look at what motivated this upgrade and what remains to be achieved if the UK is to join the A-listers.

The backdrop to the UK’s upgrade

The 13th annual edition of the Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index Report3 (the Report) is the most

comprehensive version yet, of this closely followed publication. Employing an A to D framework, calibrated on a

scale of 0 to 100, to independently evaluate 43 pension systems against more than 50 adequacy, sustainability

and integrity (or, more accurately, security) factors, the influential report covers almost two-thirds of the world’s

population.4

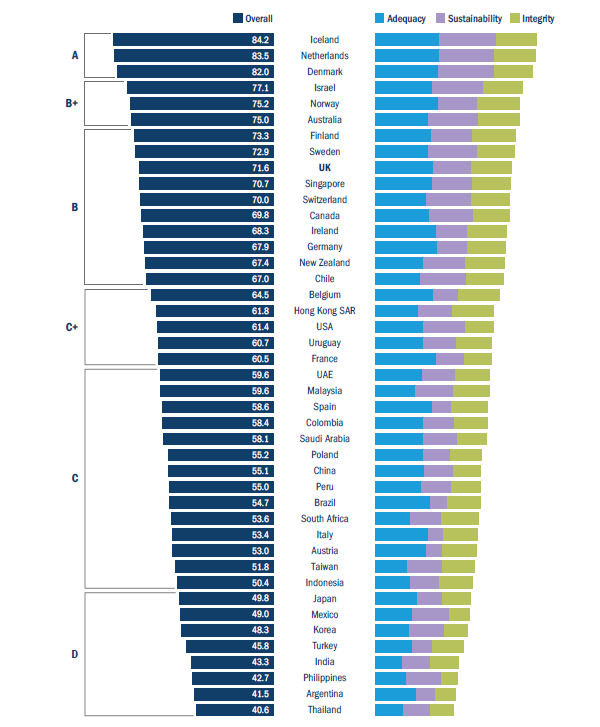

Figure 1: Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index Report 2021 results

Source: Mercer (2021) Highlights Report p.2 and Mercer (2021) p.6 (extracts).

As Figure 1 shows, the coveted A-grade, which signifies “sustainable and well-governed systems, providing strong

benefits to individuals” was, once again, awarded to the Netherlands and Denmark, though with the top spot this

time being taken by, newcomer, Iceland. However, it was the UK’s, three pillar, pensions system which, in being

awarded a B-grade, registered the biggest improvement of the 43 systems, jumping from 15th place in 2020 with

a C+, to 9th in 2021, recording its highest-ever score of 71.6.5

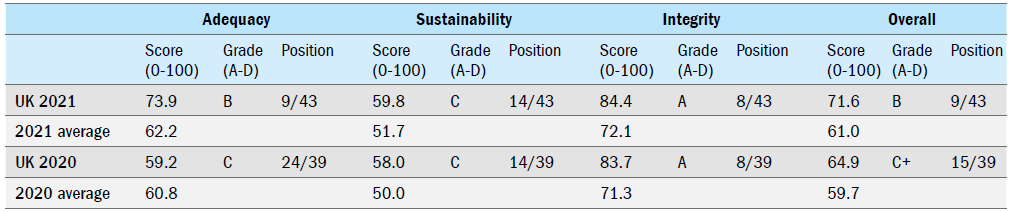

Figure 2: The UK now scores highly for both adequacy and integrity but still not sustainability

Source: Mercer (2021) Extracts from Table 3 p.7, Table 4 p.16 and p.48. Mercer (2020) Extracts from Table 2 p.7, Table 3 p.8 and p.45.

As Figure 2 shows, the UK’s strong overall showing was supported by yet another solid integrity score, bolstered

by a dramatic improvement in its adequacy credentials but was, once again, tempered by continued weakness in

its sustainability rating.6

This bounce back was ultimately attributable to two main factors. Firstly, the UK pension system’s adequacy

score was given a welcome shot in the arm by a projected increase in future net income replacement rates.7

This stemmed from a combination of the State Pension age (SPa) increasing, in October 2020, from 65 to 66,

thereby lengthening the term many people will spend in the workforce contributing to their pensions, continually

improving auto enrolment (AE) coverage and the increase, from 5% to 8% in April 2019, in the minimum AE

contribution rate feeding through to pension pot sizes. Secondly, the UK system’s integrity rating was given

a boost by the Pension Schemes Act 2021 introducing measures that permit a redistribution of risk between

employers and members,8 notably allowing Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) schemes to operate, and

providing yet more protection to pension savers by extending The Pension Regulator’s (TPR’s) powers and

access to information.

But there’s still work to be done

However, as in 2020, this year’s Report suggests that the UK’s overall index score could be further improved

by implementing four measures.

Firstly, by further extending the coverage of employees and the self-employed in private pension schemes, to

reduce dependence on the state pension.9 Indeed, as we noted in Pensions Watch edition 12 (September 2021),

despite 10.5m people having been auto enrolled into an occupational pension scheme since 2012 and almost

1m re-enrolled, a not insignificant 10.1m of the UK’s employed population are now ineligible for AE as a result of

their age and/or level of earnings – with a disproportionate number of these being women.10 Indeed, the Report

notes that the UK has the 4th largest gender pension gap of the 43 pensions systems analysed.11 Moreover, few

of the nation’s 4.4m self-employed, who are also excluded from AE, have any notable pension provision.12

Secondly, given the Report’s long-held belief that the fundamental basis of any pension system is to provide a

secure income stream throughout retirement, the Report recommends that the UK ensures that at least 60% of

accumulated retirement benefits are taken as an annuity. However, this comes at a time when, post freedom and

choice, annuitisation in the UK has hit an all time low.13

Finally, the Report suggests that the UK raises the minimum pension, or the pension credit top up, for lowincome

pensioners14 and for households, in general, to reduce their indebtedness.15 Interestingly, unlike in 2020,

the Report doesn’t mention the need to further increase the minimum AE contribution rate, despite widespread

industry calls to do so.

Suffice to say, the UK is not alone in still having work to do, as even the A-listers – Iceland, the Netherlands

and Denmark – have yet to achieve pension perfection.16 Indeed, the Report notes that, “There continues to

be a range of reforms that can be implemented to improve the long-term outcomes from retirement income

systems.”17

Why does this matter?

Despite the challenges, now is not the time to put the brakes on pension reform – in fact, it’s time to accelerate it. Individuals are having to take more and more responsibility for their own retirement income, and they need strong regulation and governance to be supported and protected

Dr David Knox, Lead Author of the 2021 Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index 18

While, against the backdrop of secular demographic headwinds, mounting environmental, social and governance

(ESG) risks and acute macroeconomic challenges, pension perfection is hard to achieve, continued reform is

needed if good retirement outcomes are to become the norm. Indeed, as the Report acknowledges, “There is

no perfect pension system that can be applied universally, but there are many common goals that can be shared

for better outcomes.”19

With this in mind, and as noted in recent editions of Pensions Watch,20 there is still much to do if the UK

pension system is to be put on a more secure footing, akin to that of the A-listers. Of course, advancing the UK’s

sustainability score, in particular, will be key to generating consistently good retirement outcomes. That said,

the direction of travel is certainly positive, with momentum building around widening auto-enrolment eligibility

(ultimately resulting in greater inclusion of the disenfranchised and a narrowing of the gender pension gap), the

forthcoming simplification of annual pension benefit statements, the imminent testing of the pension dashboard

(the launch of each resulting in prospectively greater pension saver engagement), not to mention fiduciaries’

compliance with ever more stringent ESG regulations (prospectively leading to more sustainable outcomes).21

So while several key challenges have already been overcome, evidenced by the UK’s elevation to a prestigious

B-grade, other, equally complex, challenges must continue to be addressed if the UK is to secure consistently

good retirement outcomes and ultimately achieve a coveted A-grade.